by Carlito de Corea

If you like to watch films that reflect the difficulties of ordinary life, the pain of true loss, and then some hard fought redemption, or perhaps resulting ruin, something that you can relate to, see your own suffering in, then Cameron Crowe's new movie, Elizabethtown, will not be for you. If, on the other hand, you simply like to escape daily life and enjoy a good movie with a good story, then…no, maybe Elizabethtown still won't work for you.

The film begins with Drew Baylor, played by Orlando Bloom, making his way toward an expensive looking corporate office, the headquarters for Mercury, the shoe manufacturing giant for whom he works, perhaps a parody of Nike. We realize something is not right for him as he enters the building and makes his way through the palatial concourse toward one of the building's boardrooms, where we sense some terrible fate awaits him. “I'm ok,” he says repeatedly to some of the people he passes. This peculiar behavior sparks an urge to laugh out loud, as it clearly implies the opposite, that he is not okay, and that he is walking toward some monumental disaster. I have to admit that this movie did hold my attention for a few minutes, and that I did laugh out loud. I wondered what in the world was going to happen to him. I was ready to sympathize, to empathize, as yes, we too feel the weight, daily, of the corporate bullies crowding us out, shrinking our burgers and raising the prices on everything we come near. And we don't even dare to think of actually working for them. Yes, this could be good. Drew is our whipping boy. Go get 'em, brother.

After sort of being informed by his boss, played by Alec Baldwin, that he would be taking the fall for a particular line of shoe that has lost the company nine hundred and something million dollars, and to which he was closely linked, if not entirely responsible for, Drew returns to an expensive home, as progressive looking as his office, and begins to rig his stationary exercise bike with a huge kitchen knife that will stab him through the chest when he turns the machine on. The tension is humorously released when his cell phone begins vibrating on the kitchen table. Annoyed and not even able to commit suicide properly, he succumbs and answers this one last call, only to find out that his father has died and that his family is now relying on him to go to Elizabethtown, Kentucky, to take care of funeral arrangements, and straighten things out with his father's side of the family. Unfortunately, the initial feeling that any number of incredible and unexpected things could happen to this character soon gives way to a litany of trite, uneventful circumstances. The pathos in this early sequence is never returned to again, and soon after it the film begins to lose its integrity.

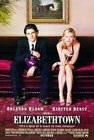

His suicide postponed, Drew is now forced back into the arena of life, and so embarks on what is the main narrative of the story, heading into the past while trying to work out the present, and meeting Claire, played by Kirsten Dunst, and falling in love with her. He arrives in Kentucky to a heartfelt, near-parade of a welcome, accompanied by nostalgic music and some cool images of small town America as he cruises through Elizabethtown in his rented car. But instead of settling down into a heartfelt journey of self realization, or personal hardships and conflict, Elizabethtown digresses into an assortment of styles and loosely arranged scenes that barely cohere. We see problems early on when Drew arrives at his father's wake and the film tries to achieve a deadpan quirk, a la The Coen Brothers, laying it on thick with dumb lines and heavy pauses between them to accentuate the stupidity of the characters, of small town folk as it happens, a cliché that small-town folk, maybe even from Elizabethtown, won't much appreciate, I'm guessing. Many scenes in the film seem to be all about the attempt at this type of humor, becoming the focus of purposeless moments, like the drunken newlywed man Drew encounters while stealing beer from one of the rooms at his hotel, a scene that is not only self-conscious and contrived, and patently unfunny, but poorly acted as well. The film slips in and out of this type of irony and realism, returning to Crowe's more usual sentimental tones when the film returns to its focus on Drew and Claire.

Getting the most out of his actors, or even concern over the acting in this film at all, doesn't seem to weigh heavily on Cameron Crowe's mind. The casting of Orlando Bloom, for example, is questionable, although a whole lot better than his purported first choice, Ashton Kutcher. At times Bloom seems uncertain whether to add to the effect of irony Crowe is often trying to achieve with his own expressions, or to hold back and play it straight. But worse than this, Bloom seems throughout to possess an irrepressible confidence, even smugness, that undermines the desperation Drew is supposed to be feeling. He is simply too glib, and as I watched the film I wondered whether he might not be more comfortable with a quiver of arrows on his back or a sword and some swashbuckling pirate's outfit, winking at the camera with that confident gleam in his eye. He lacked the inner turmoil we have seen from actors like Cruise in previous Crowe films, or John Cusack in many of his performances. Bloom is a decent actor, but is perhaps miscast, or at least misdirected, in this film. He just exudes too much confidence for a man on the brink.

Before arriving in Kentucky, Drew has encountered the already-loyal, undyingly enthusiastic Claire, the only stewardess on a flight where he is also the only passenger. This encounter, which most of us can of course relate to, signals perhaps the biggest problem with this film. There is utterly no conflict. In Elizabethtown everything works out, and nothing acquired comes with any difficulty. Drew simply breezes through one scene after another with everything falling into place as he goes. There is no loss, no pain, no catharsis. Where's the recoil from the loss of a billion dollars? And Claire, despite being an airline hostess whose job it is to travel all over the country, always manages to be there beside him at his hotel in Kentucky, where he is either in the process of preparing for the memorial for his father or arguing with his father's side of the family over whether to cremate his father's body or have him buried in the traditional way. And she understands him…fully. Throughout the film we simply watch them come to like each other more and more. The closest their relationship ever comes to danger is when Drew appears for perhaps fifteen seconds to be distancing himself from her because of his inner turmoil over losing Mercury a billion dollars. She responds, as with all things she discusses, by basically saying she understands everything. Problem solved.

The film crescendos with a banquet, where the tension of a vague subplot relating to some long held feud between Drew's mother, played by Susan Sarandon, and father's side of the family, is finally released. But this moment only highlights, once again, that Crowe has little control over his material, or has poor material he is trying to give meaning to. The latter seems closer to the truth. The film at this point is supposed to have some cathartic significance, with Sarandon's character delivering a speech in the form of a comedy routine, because…she's been taking standup comedy classes…because…well, she's been working stuff out. Somewhat on their own among the Kentucky side of the family, Drew's immediate family experiences a collective catharsis, as Drew and his sister sit at a table at the front of the hall surrounded by the slightly hostile relatives and nervously watch their mother deliver a eulogy that comes dangerously close to being inappropriate and threatens to pull them even further out of the family's ambivalent graces. Fortunately, however, their mother wins everyone over with her routine and once again everything works out. The only problem is that Sarandon's comedy routine is inappropriate and completely unfunny, so idiotically inappropriate and unfunny that the only way any group of people under any circumstances would have laughed at it is if they had been under the influence of LSD.

As with many “nice” moments in the film, they often seem to have been conceived separately, and based rather on a preference for particular songs than on concern for the overall coherence of the work. Crowe almost seems to direct around his desire to highlight some of his favorite music. Claire and Drew's musically accompanied skip through the graveyard, for example, seemed particularly irrelevant to the film. The music itself too often seems to be the film's lead character, and one gets the impression that ideas for his movies come to him while he's listening to a particular song, and that he can't resist putting those scenes into his films, along with the songs that inspired them. Admittedly, some of the images are beautiful and combined with his taste in music, which is also good, create moments that lift us up and make us want to rock out with the picture, with his sentimentality. Unfortunately, there is nothing to fall back on. We realize, after time, that the picture is just that-a lot of rock and roll imagery without much substance.

Of course, through all of this non-turmoil Claire is waiting in the wings, but, for god knows what reason-there having been no real indication in the film so far that he would choose not to be with Claire-we are now made to understand that Drew is just not sure of what the future holds, and needs to go off on his own. Do some soul searching. Claire, ever-faithful, bids him good luck and sends him on a rock and roll Easter egg hunt across the country. She has left him with a selection of music and directions for great rock and roll landmarks to visit, accompanied with her ragamuffin scrapbook full of sentiments and philosophies, as well as a trail of clues toward the end of his journey that will lead him back to her, back “home.” The final clue, a note left in a running shoe-yes the very one he is infamous for-in some shopping mall or market, has him turn around to see Claire standing there in the crowd, waiting for him as always.

This final, irrelevant touch is simply too much, and hits us with the force of a Vogon poetry reading. Elizabethtown is unbearable. Even for people with a sweet tooth, I don't think this film will work. By the end, the sugars from my snacks were coagulating in my blood and I was looking for the exits. Elizabethtown is so insipid, such a maudlin tour de force, that when the end came I was shaking my head in disbelief, desperate to get out of the theatre, to go and do something about the sickly sweet feeling coursing through my veins-take some medication, walk it off somewhere, discuss it with an anger management group, or maybe even talk to a police officer to see if there was any legal recourse, some way to retrieve that ten dollars. “Hey, man, those guys just ripped me off.