by Carlito de Corea

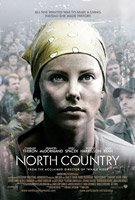

Misogyny is the theme in North Country. Based on a true story, the film tells the story of Josey Aimes, who takes on the Pearson Mining Company over allegations of sexual abuse. The story begins in the courtroom, where Josey, played by Charlize Theron, is answering a series of degrading questions. The film flashes back to where it all began, intermittently returning to the courtroom until the story is under way.

The story proper begins with Josey leaving home, with her kids in tow, to stay with her parents because of domestic abuse. The husband in this case is generic. We never see him, except obscurely when Josey is fighting with him on the lawn of her parents’ home almost immediately after leaving him. This scene is a strong indicator of how things will go, both for Josey, and for we the viewers, as her father watches without helping and makes cynical remarks about her being a troublemaker. The tone is heavy from the start and never lets up, until the end, when it swings wildly in the other direction, to a sentimental catharsis in court that ultimately ruins some small ground the film was beginning to regain.

Back in the courtroom, the company’s attorney asks Josey when she first started working at the mine. We flash back to a local bar where she first meets her friend Grace, played by Frances McDormand, a union rep and employee of the Pearson Mining Company. Over a beer and a game of darts they become friends and shortly thereafter Josey is also working at the mine. From here the film describes excruciatingly the degrading conditions the women at the mine have to endure: endless litanies of derogatory, sexually explicit remarks and unwanted advances by their male co-workers.

A recent court decision has forced the Pearson Mining Company to allow women to work at the mine, and, as a result, new female recruits experience open hostility and resentment. They are also subject to the constant threat of rape. “Cunt,” one man says under his breath, passing Josey in a hallway as she is being led to her first assignment. “Who’s gonna be my bitch?” another man says just after this, as their foreman turns them over to another employee for work detail.

Things get so bad that Josey is forced to quit her job at the mine. She decides to take legal action and enlists the help of Bill White, played by Woody Harrelson, a lawyer and friend, and one of the only two males realistically portrayed in this film. Josey encounters resistance from everyone, including her own family—namely her father who himself has worked at the mine for most of his life—and from the women who still have to work there and don’t want to make waves. She tries to get her fellow employees to stand with her, to stand up for what’s right and make it safe for women to work at the mine. She only needs three more women to join her and her case can be filed as a “Class Action” suit, setting a legal precedent and giving them a better chance of winning.

While the story and theme in North Country are interesting, and the film is at times moving, its portrayal of misogyny is unfortunately too cynical and exaggerated. From the start we are subjected to a constant barrage of unrealistic male characters. With one or two exceptions, the men in North Country are all menacing sociopaths, one-dimensional characters with no moral fiber whatsoever, their behavior more closely resembling that of prison inmates. So much focus is put on describing men as leering, salacious pigs—it seems like there is one waiting around every dark corner—that the portrayals become cliché, over the top, and we are no longer interested in them, except as comic book villains whose only purpose it is to draw us cheaply and reflexively into condemning bad people and cheering for the hero of the story.

The pitch of negativity reaches its climax at a company meeting devoted entirely to deriding Josey and further ensuring that everyone remains against her so that she doesn’t win the lawsuit and everyone can keep their jobs. Bobby Sharp, played by Jeremy Renner, Josey’s primary nemesis, and part of a subplot which I won’t reveal, delivers a speech full of derogatory expletives directed at Josey that has the entire town hall hooting and hollering over her demise. Josey enters the meeting with her lawyer and friend, Bill White, summoning the courage to speak out and demanding her right to speak at the microphone, whereupon she is booed and jeered and told to get lost. Determined not to give up, Josey carries on, making her way to the podium amidst the deafening clamor of crude remarks. She tries to appeal to the hardened crowd, delivering an emotional speech that for a moment seems to be having an effect. Surprisingly, the miners stop booing and we wonder for a moment if she might not turn the crowd in her favor. But once again the jeering starts.

“Hey Josie, show us your tits,” one man shouts, triggering another deluge of lewd remarks.

Having had enough, Josie’s father, Hank, played by Richard Jenkins, walks to the podium and instructs his daughter to hand over the mic. Crushed and no longer able to defend herself against what could prove to be the ultimate final insult, she stares at her father helplessly, pleadingly. Is he really going to silence her, we wonder. Or might he possibly, finally defend his daughter against this lunacy. We are overcome by a long needed release of tension when Hank takes the microphone from his daughter and rather than walking away takes a place beside her at the podium. Both Theron and Jenkins deliver powerful performances in this scene, and like Pavlov’s dog I responded to it. But I did so begrudgingly, aware all the while that this basic and obvious component of compassion was artificially withheld from me in order to achieve this effect.

This scene also had the unfortunate effect of reminding me why much of what I had seen so far was now even more implausible: HER FATHER WORKS AT THE MINE AND HAS FRIENDS THERE!!! Most men do not badger and sexually harass their friends’ daughters, or their colleagues’ daughters, and most likely would not put up with it from other people as well. I personally don’t know any men who wouldn’t at least say, “Hey watch your mouth,” when someone was calling his friend’s daughter a bitch and a whore. The scene also ends with another unlikely occurrence. Everyone starts clapping after Hank delivers his speech, in which he told them how ashamed he was of them all and that he had no more respect for them. Why would you cheer your own denunciation?

At this point, however, complaints of inconsistencies at the town hall meeting aside, I felt that the film was becoming more reasonable and might become more interesting. That is to say that some of the key characters were becoming human, finally, and the film, subsequently, more realistic. There is a nice moment when Josey is back at home with her father and mother, played by Sissy Spacek, and the family finally seems to be coming together. Her father gets up from the table at one point to embrace her when she breaks down and says she doesn’t know if she can take any more. As well, there is a tender moment between herself and her oldest son, Sammy, who finally seems to relent after feeling resentment and hostility toward his mother for the pressure that her infamy has put him under. Unfortunately, however, the film then swings too heavily toward the sentimental, delivering a soppy courtroom ending that borders on the absurd, and shows as much insight into courtroom proceedings as it does into male psychology.

A good cast makes much of the exaggerated treatment of this subject bearable, and I admit to being drawn into the story at times, but, unfortunately, I found myself too often wanting to be drawn in more than I was being drawn in. Too many exaggerations and a constant sense that the chips were unrealistically stacked against Josey kept me from warming up to North Country. The depiction of men in this movie was also disappointing. The type of aggression toward women described in the film should perhaps have been characterized as the exception rather than the rule, if for no other reason than to create a greater degree of tension in the film, a greater degree of balance, even if the events described really happened and the majority of the men at the mine were evil and cowardly in real life.